...because learning in Indigenous Education is place-based and grounded in gratitude and responsibility toward the land that sustains all life and the First Peoples who have cared for it since time immemorial.

Below are connections to land, place and culture that bring together new learning with previous understanding, knowing that my knowledge and awareness will grow throughout life.

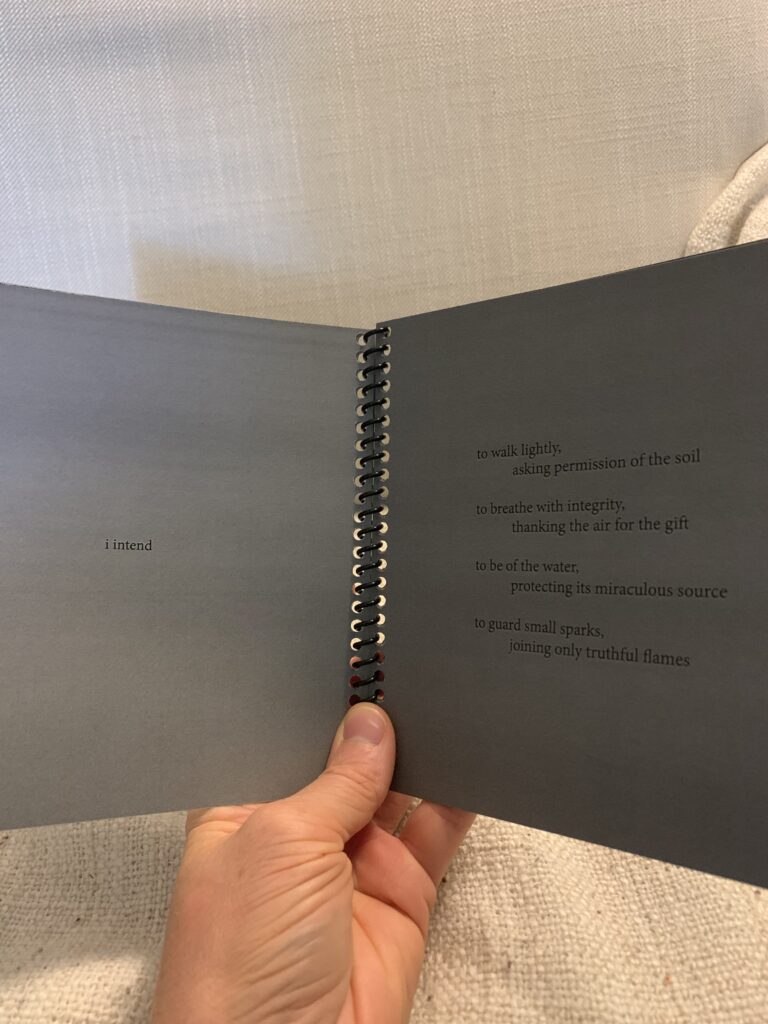

In my work and reflection, I hold the intention to honour the land where I live, the lands where I and my immediate family were born, and the distant lands where my ancestors came from. The writing of Robin Wall Kimmerer is a constant inspiration in this labour of love and imagination: “Being naturalized to place means to live as if this is the land that feeds you, as if these are the streams from which you drink, that build your body and fill your spirit” (Braiding Sweetgrass, p. 214). Because this is true.

Despite the online nature of most of our course work, taking my Master’s degree back at the University of Calgary represents a homecoming for me, a return to where I was born and returned to live many times. I am so very happy to reconnect with our instructor Dr. Yvonne Poitras Pratt, who I was fortunate enough to connect with, in 2015 and since, while working on various research projects. It was so memorable to be on the land, sitting in circle and walking together with her, our instructor Dr. Jaime Fiddler, and our classmates, supported by two amazing Knowledge Keepers, Elder Wanda First Rider, Kainai, and Elder Miss Betty Letendre, Cree Métis.

It was not a given that we would be able to connect in person, but as vaccinations became more widespread, we were fortunate to be able to gather for two days of land-based learning. To mark this honour, I decided to bring some cedar bundles as a sacred medicine offering from the forests that surround where I live and work. I harvested with the protocol I’ve been given by local Knowledge Keepers, and found just the right place, which was a small tree that looked like it had just been knocked down by a large fallen branch. It offered just the right amount for the bundles I wanted to bring. As I breathed the smoky forest fire air, I knew how blessed I was to be in company with a forest still standing in these warming times.

This was, in part, in return for the beautiful gift of tobacco seeds that I received by mail from Dr. Poitras Pratt before the course had begun. We were given instructions for growing the seeds, but it took some time for me to find the confidence to begin. As it turned out, the germinating tobacco seeds ended up being my companions for the trip to Calgary. However, they didn’t sprout until there was also an established tobacco plant beside them, another gift from Dr. Poitras Pratt and her gardener husband. The tobacco plants are now growing happily in company with the cedars that shade and protect my home.

For anyone new to learning about sacred medicines, the resources shared by Dawn Iéstoseranon:nha at Pass the Feather offer an illuminating starting point.

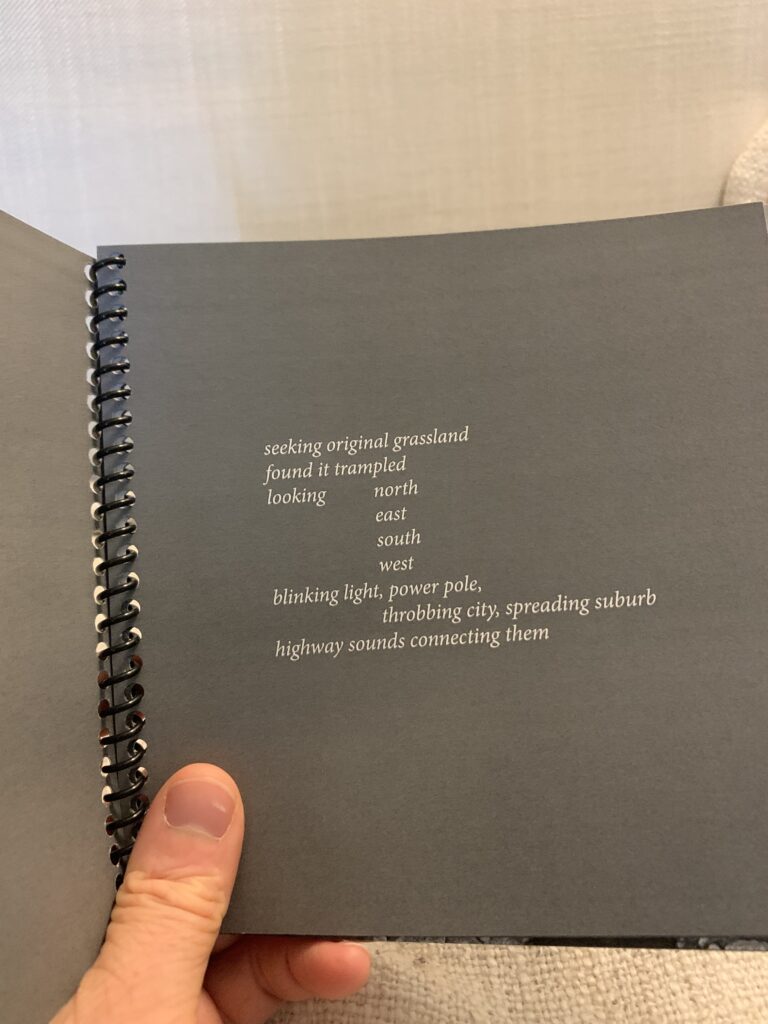

One of our most incredible experiences in land-based learning took place at the Blackfoot medicine wheel that had been built in 2015 at Nosehill park, near historical tipi rings. This was a personal returning, almost uncanny in nature, since I had gone to that exact spot in 2014, before the medicine wheel was there, but enacting my own four quadrant ceremony by looking to each direction for teachings to guide a book project for my first course in Indigenous Education.

This time, we happened to be meeting with our class at the same time as many members of the Siksika Horn Society were also there in ceremony, some of whom had built the medicine wheel. We were invited to join them in offerings and prayer for the current hardships being experienced by their people, and were told by Elder Striped Wolf, “we are from many nations, but we are one.” We continued our learning with Kainai Elder Wanda First Rider afterward, who shared Iniskim, or sacred buffalo teachings, as well as star teachings connected to the number seven. Elder Miss Betty Letendre also connected to the importance of the seven teachings in Cree culture, and they both reinforced how fortunate we were to have had the chance to participate in ceremony with the Siksika ceremonialists.

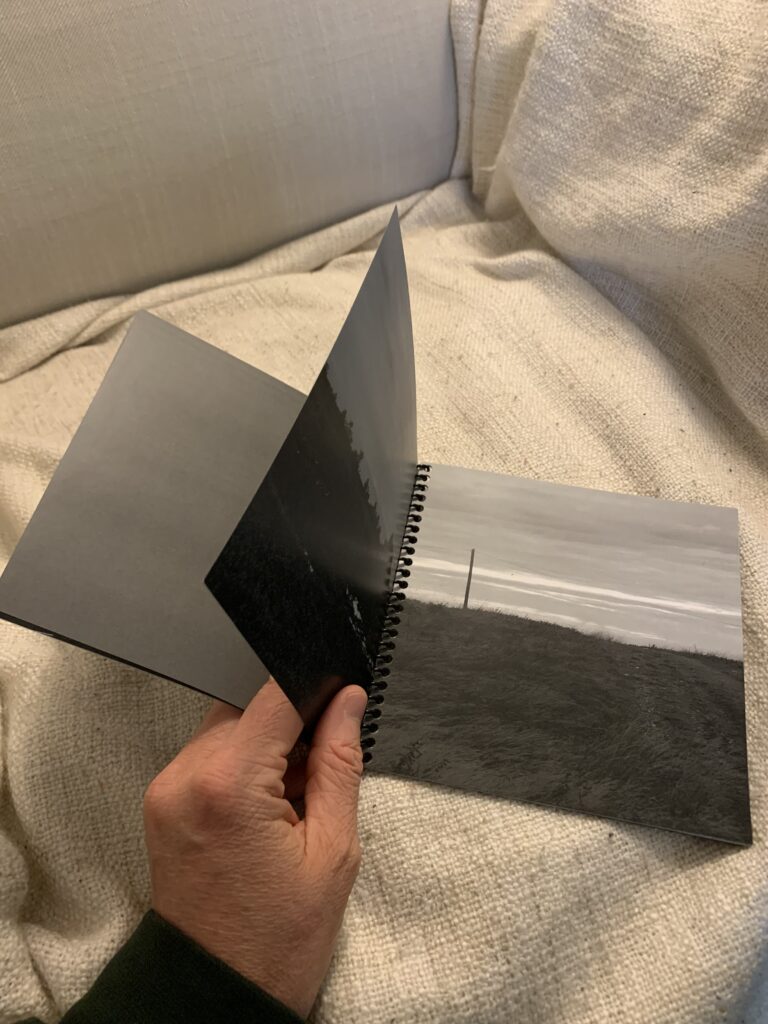

These were meaningful shared experiences bringing us together as a full group. They were also continuous with independent land-based learning I had been undertaking back in BC to respond to prior assignments. Learning Task 3 was a described as a visual essay answering the question “what does decolonizing mean to you?” At the suggestion to work with a unifying theme, I was inspired by a Katherena Vermette poem “this country has an other story… it is written / in water / carved on earth” from her recent book river woman (2018, p. 61), to follow the trajectory of water from our neighborhood creek down to where it flows through several dams near the schools where I work. The personal definition of decolonization I arrived at through this assignment is as follows:

“As a settler, decolonizing is awareness and refusal of the colonial mindset through worldview learning, ethical relations and critical hope for a better future.“

The imagery and quotes below share aspects of the path of discovery that led to this definition, which will serve me well for the work ahead.

The water told a story of the damages caused to the land caused by the colonial mindset and its tendencies toward exploitation, domination, control, disrespect, apathy, ignorance and numbness. From a quote from my paper, this also “recalls violence in society such as the exploitation of young Indigenous people in human trafficking, and missing and murdered women, children and two-spirit people. Domination, control and disrespect connect to the pass system (Williams, 2015) and the treatment of children and families during the residential school era, sixties scoop and current social services. Beyond settler apathy and ignorance there is also deep numbness to the harms inflicted on people and the land. The history panels are located near a natural marker known as Coyote Rock, which is said to have been the highest point of salmon’s incredible passage from the Pacific and an important First Nations gathering site. An accurate history would grieve the cultural and ecological loss; propagating blank spaces of memory and awareness is terra nullius still at work (Cariou, 2014).

However, in seeking critical hope to give direction beyond the pull of despair, it was important to notice that the water is still flowing powerfully despite the many barriers that confront it. I was also given additional insights by an osprey mother protecting her nest near one of the dams. She seemed to say, that faced with all the devastation that colonialism has brought, what matters most is our responsibility to protect the babies and all that sustains them.

The osprey mother became the iconic image I would use to represent my visual essay, and I decided to work with the image in acrylic paints, including liquid pouring to represent water and invite its fluid energy into the process. The day that we photographed her was very hot and sunny, but still clear. By the time I was finishing the painting, forest fires were threatening across the province and the air quality was keeping us indoors. It felt like a relevant conceptual addition to include the smoke, so I updated the painting after the assignment deadline. I may still work on it further, as I seek to reclaim more hope from an otherwise distressing circumstances. Thankfully, several weeks later, we have now had a day of rain which has made the situation feel less dire, even though the fires are still burning.

In the depth of learning involved in connecting to land and culture, I was reminded that I must “stay connected to my own worldviews, so as not to become lost, or drift into appropriation. Braiding Sweetgrass brings an anchor point; as Kimmerer highlights the Anishinaabe “one bowl, one spoon” principle of sharing to maintain abundance (2013, p. 376), I remember my Swedish relatives’ way of being, and the concept lagom, which means saving enough for everyone (Nackagubben, 2017). Retrieving any teachings from my own ancestors that also refuse the colonial mindset is another way to honor ethical relations.” This was one of my closing points for the essay, and also returns me to the idea that to live “naturalized to place,” I also feel drawn to connect with the land of my ancestors.

So far the only ancestors I am able to trace to a particular land in Europe are my maternal great grandparents, who came from Offerdal, a tiny hamlet in Jämtland province, Sweden. I will visit there one day and see what reconnections I may be able to make, but for the time being, I am comforted to know that I have chosen to raise my family in a land of lakes and forests much like my ancestors left back home. In this way, taking care with the land and water here connects me to those in my family line who did not leave their Indigenous lands.

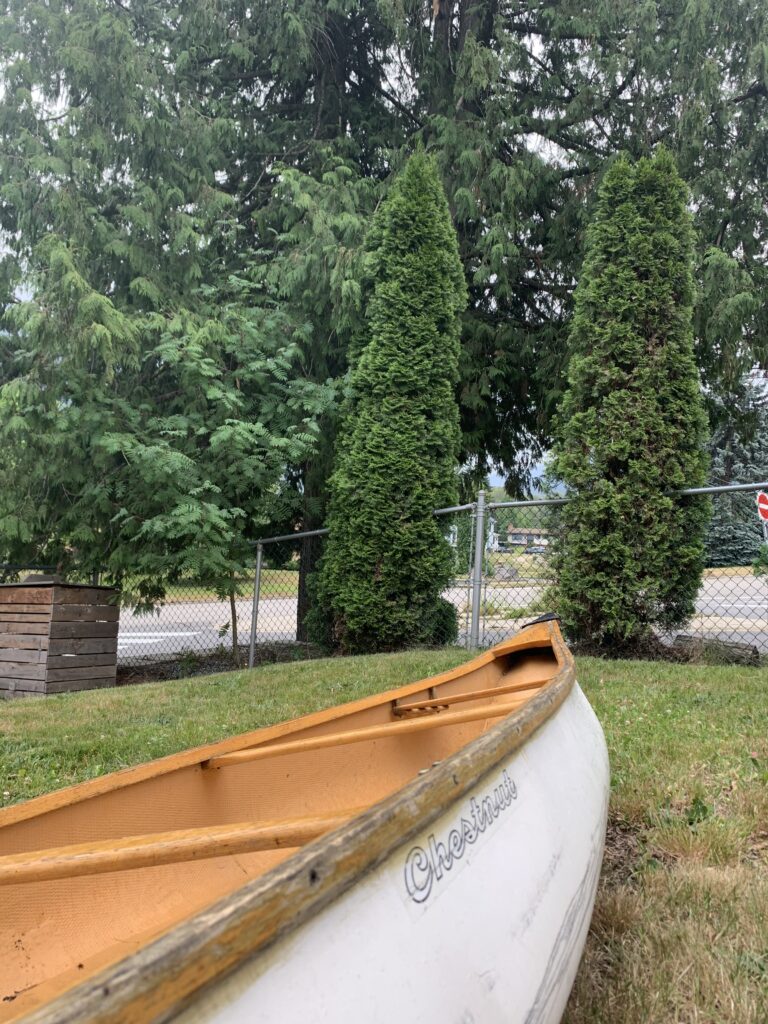

In one of our earliest classes, we were asked to take a short break to take a photograph outside our homes in answer to the question “how does where you learn influence how you learn?” My image below, of our family canoe, not yet put away from a weekend adventure represents my answer to this question. I believe that I learn land-based cultural teachings more easily because of my proximity to these trees, forests and beautiful clean waters. The canoe represents the value we hold as a family to learn about the land, connect with it and participate in its protection. Significantly, it is the same canoe that my parents used when I was a small child, and I am now committed to also using to share a love for the land with my own child. Where we spend time learning important lessons as children gives us rich memories with all our senses, making those same landscapes resonate for us as learning contexts throughout our lives.

Since so little of our pre-settler culture has been preserved for us to learn from, perhaps the land can teach us some of these lost lessons. The Jämtland pre-Christian culture was based in moose hunting and bear rituals, until around the year 1040, when the witch hunts and associated domination finally suppressed their Indigenous beliefs. Alexia and I made the thin bread recipe that comes to us from our Jämtland relations for my introductory cultural artifact to present in our second Call to Action class. Doing so, we can picture women in our line who had ancestral songs, medicinal knowledge and sacred practices to honour the land. This helps us to refuse the colonial mindset through ancestral knowledge, not just worldview learning from other cultures, and contribute to the personal and family healing of the colonial mindset that in some small way supports community and global transformation.