In addition to the teaching and support roles I fulfill in a K-12 context, I also commit to volunteer work as a community educator, as one way to give back for all that I receive. It is in these spaces that I am working on a capstone project to complete my year in the Indigenous Education: A Call to Action program toward an eventual Masters of Education degree. During the autumn months, we developed our understanding of critical service-learning through readings and theoretical inquiry with our classmates. Meanwhile, we were also in conversation with community partners, designing a service-learning project to be completed during the winter semester.

Formally, my community partner is the Nelson Public Library, but the project we are imagining also builds upon informal relationships with Indigenous individuals and organizations in our complex region. There is local momentum to expand upon the physical presence, and the role and reach of the library as a public-service institution. Library leadership is committed to doing so within a growing decolonizing intention, so my service role is to bring my experience in reconciliatory pedagogy to support their learning and exploration processes as they take steps in this direction. A key guide for our work is the Truth and Reconciliation Report published by the Canadian Federation of Library Associations.

Partnering formally with a settler institution, I am taking up the call issued by such speakers as Jesse Wente (2021), Anishinaabe broadcaster, writer and Arts leader in which he asked “white people to talk to other white people… (since it is difficult) for our communities to always have to engage in sort of 101 is that a lot of allies could actually do that lift that burden for us” (2:55). This was communicated in a recent Suzuki Foundation video regarding Land Governance for the future, and resonated as an intention since I live and work in unceded territory with complex and unresolved multi-nation governance, where direct collaboration opportunities are rare. While imagining possible project parameters within this frame, three key resources from our current courses’ assigned list have offered guidance in considering the questions below:

- What can I learn from other service-learning projects?

- How do the approaches with other projects influence or help me define my own approach to service learning?

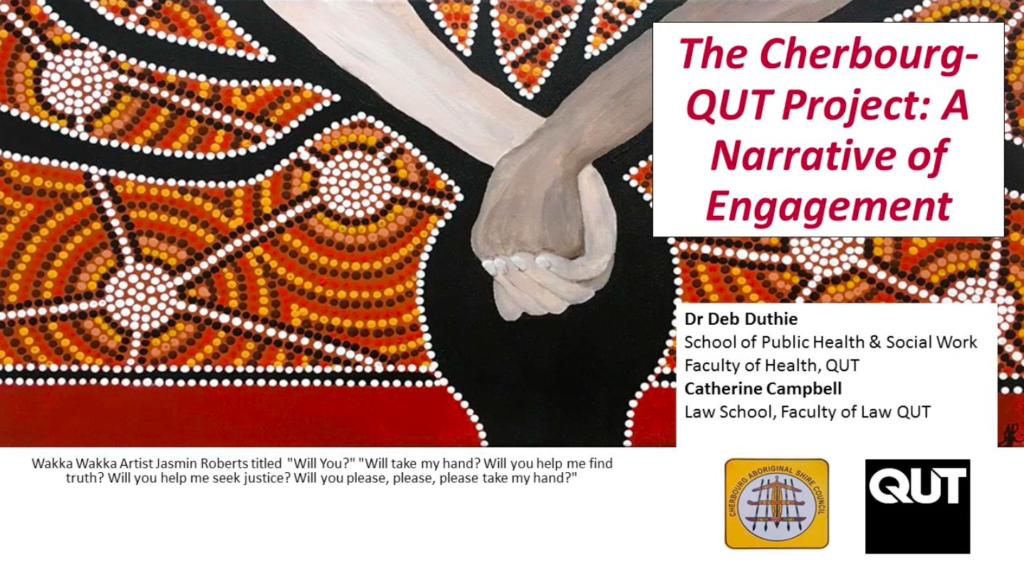

1) CEWIL Canada webinar – With our developing intention to support community learning while also embarking upon decolonization processes for the library, a 2019 webinar with Dr. Deb Duthie and Catherine Campbell published by CEWIL Canada was particularly instructive. It addresses a Queensland University of Technology service-project in Cherbourg Australia, in which privileged law students are supported and guided by more experienced community builders. They then bridge the physical and experiential distance from their own lives to build relationships with the Indigenous community at Cherbourg, located three hours away. The town of Nelson, more than two hours away from the nearest First Nations community, holds similar challenges and opportunities.

Each year, the Cherbourg project includes service elements guided by current community needs, however relational learning is the larger part of the program, seeking ways to work responsibly while building “increased knowledge of Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing” (Duthie & Campbell, 2019, 47:20). Students emerge with a greater understanding of community norms, with the ability to form authentic relationships in community, and in some cases have ended up staying to work as valued members of the community.

Our local project echoes this focus on worldview learning, and can be guided by one of the CEWIL presenters’ statements “in service-learning, the hyphen stands for reflection” (Duthie & Campbell, 2019, 57:52). The presenters provide further guidance, listing the following reflection topic areas: “reflecting on the skills they have, and what they’ve learned, and how they can use that in their future practice” (Duthie & Campbell, 2019, 58:11). In this description of the service project, I see myself in both the students and the program facilitators, as I will need to continually reflect upon my own relational learning in community, while also supporting reflective practices among other non-Indigenous project participants.

The other key element of the CEWIL project that will guide us, is the similar profile of very segregated communities, valuing the priority to carefully and consciously desegregate. Similarly, we wish to do so within a frame of continual learning, both about the truth of history, and “about ongoing impacts of historical and current discriminatory trauma” (Duthie & Campbell, 2019, 55:09). We understand that to be successful, we must be committed to “cultural humility, (and) exploring culturally safe practices to learn how to not cause harm” (Duthie & Campbell, 2019, 35:29).

2) “Making space”: Lessons from collaborations with tribal nations. In this 2011 article by Erich Steinman, the writer provides concrete direction regarding the areas of tension that can arise when learning Indigenous ways of being. His reflections reinforce the notion that knowledge alone will not foster the transformative change we wish to see in society. The service-learning program he draws from involves direct and long-term collaboration with a Nation, providing a context that is “deeply intercultural, counterhegemonic, and decolonizing” (Steinman, 2011, p. 5). This kind of collaboration is not yet accessible in these lands, but provides learning and inspiration of what possibilities may open up in future through the beginnings in learning and community action of our current project.

The writer reflects that before, beyond, and even at the exclusion of action-oriented goals, the concept of “making space” illuminates that the priority “was to “be” with the tribal members at the tribal headquarters, and to build rapport, familiarity, friendship and trust” (Steinman, 2011, p. 6). He argues that many non-Indigenous participants experienced discomfort within this expectation, and that post-secondary institutions need to recognize the crucial nature of these processes, given that “a number of dynamics facilitated by the making of space… are critical and substantive, rather than just symbolic” (p. 6).

The conceptual themes that Steinman calls attention to for learning Indigenous ways of being include: everyday social norms, relationality and relational pacing, reciprocity, respect for protocols, non-linear understanding of time, egalitarian dynamics, the foundational presence of spirituality and ceremony, and the importance of both witnessing, and participatory listening. He also summarizes the nature of Indigenous teaching and learning as grounded in layered storytelling while being “contextual, holistic, community-oriented, and relationship and place-based” (2011, p. 10). This provides guidance both for my own roles as learner and an educator, as well as the library’s community education role.

Steinman (2011) affirms that all of this understanding needs to be developed within a frame of respect for Indigenous sovereignty and nation-to-nation relationships. He reflects upon the relational goals of one particular project, recognizing that the “emergent premise of our exchanges with the Makah was that the problem was located in the broader society, not with the Makah” (P. 9). From this re-balanced lens, relational learning took on the appropriate weight and importance required to begin the work of building mainstream understanding for the cultural practices of the Makah community. The community perceived this as service unto itself.

Nonetheless, Steinman’s (2011) nuanced analysis also beautifully articulates the need to extend beyond either-or struggles to recognize the Indigenous “alternative moral imagination that disrupts the Indigenous/settler binary, itself a foundation of colonialism” (p. 12). We will be well-guided by returning again and again to the detailed touch-point provided by the “making space” concept, and this article’s interpretation of the necessity to learn by relating.

3) Overview of the social justice model for service-learning – In this chapter by Susan Benigni Cipolle (2010) within her book Service-learning and social justice: Engaging students in social change, she expands with greater detail upon a concern that also comes up in the Steinman (2011) piece above; identifying that service can often be “consistent with a rescuer-saves-victim dynamic” (Steinman, 2011, p. 7).

Cipolle (2010) recognizes that there can be a progression achieved among privileged service-learning participants by cultivating toward more ethical and effective engagement, from charity, to caring to a social justice orientation and finally to mature critical consciousness. She also emphasizes the importance of reflection, “centered on understanding how power and privilege operate to the advantage of the dominant class and to the exclusion of others” (p. 14).

This also reinforces the orientation present in the two previous resources, that critical service-learning requires “going beyond learning about others, most emphatically beginning with learning about yourself… your beliefs, attitudes, biases and assumptions; assessing their origins…” (Cipolle, 2010, p. 6). The guidance this article offers for our community project is to continually locate ourselves, and others who join in the work, relative to existing power structures, furthering “lifelong commitment to work as allies with oppressed groups, to understand the root causes of injustice and take action to make the system more equitable” (Cipolle, 2010, p. 13).

At right, a personal symbol of social justice developed through reflection and dialogue within the Nelson Library circle while reading the book Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World, Tyson Yunkaporta.

In summary, the three resources analyzed above help me to define my priorities for the service-learning project to include: learning and teaching about Indigenous ways of being, engaging with desegregation and conscious relating, as well as critical self-reflection relative to social justice action. I am grateful to the Indigenous Education: A Call to Action program, and all the learning and resources it has provided like those above, allowing me to better understand my capacities and responsibilities as a change agent. It is also helping me to see with greater clarity how I may support others to step into this responsibility and strength.

The above writing has been in fulfilment of EDER 655.17 Critical Service Learning and Engaged Scholarship in Indigenous Education, and the references for this work are included in this document.