…because for all other interests and themes, the work of decolonization requires a heart deeply invested in pursuing social justice, including all its personal and systemic implications.

Entering an era of deepening truths bringing grief close to the surface as the remains of children in unmarked graves are brought to light across the country, we look to the wise voices of such guides as Murray Sinclair, former senator and chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In this recent video he emphasizes that this process is necessary as one more important step for Canadians to understand the “magnitude of responsibility” that exists to understand the full truth, support survivors and intergenerational survivors, and ultimately transform our society. As someone who carries the privilege of whiteness and the ancestral benefits of settler colonialism, it is my responsibility to listen deeply and take ongoing action to dismantle the societal mechanisms of inequity that continue to cause harm. The personal definition of decolonization I arrived at in the Land & Culture section of this site will continue to guide me.

“As a settler, decolonizing is awareness and refusal of the colonial mindset through worldview learning, ethical relations and critical hope for a better future.“

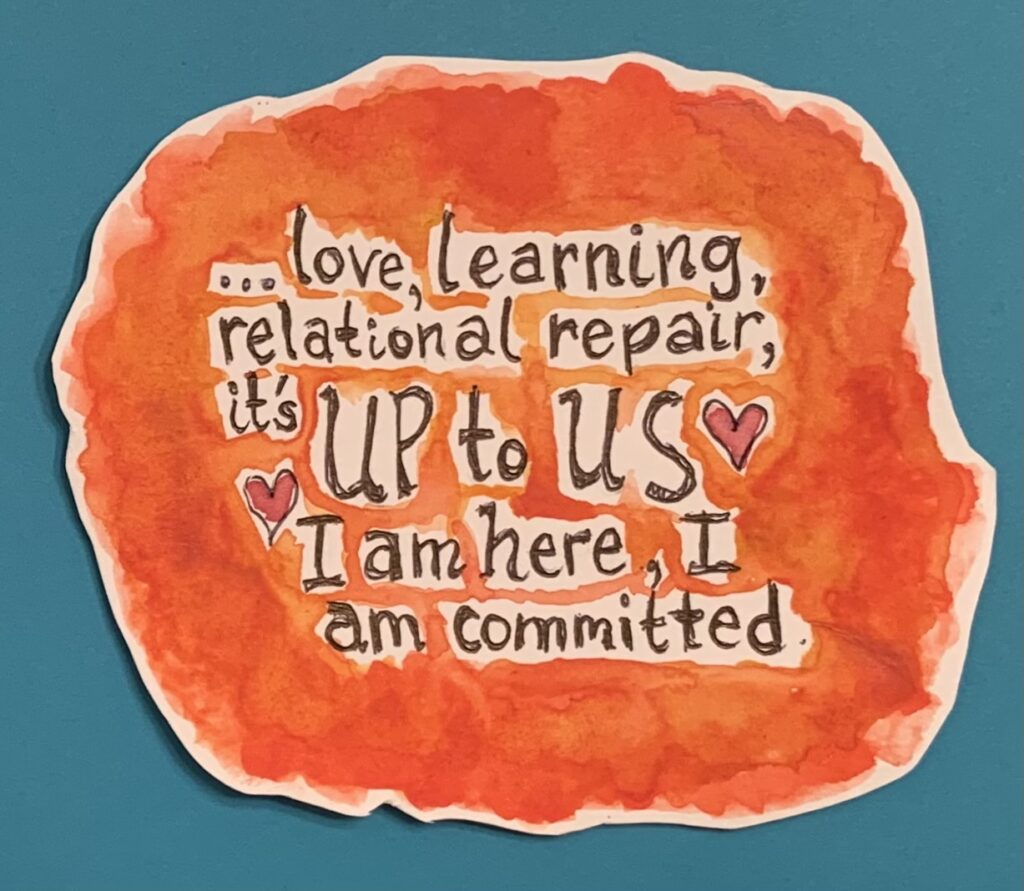

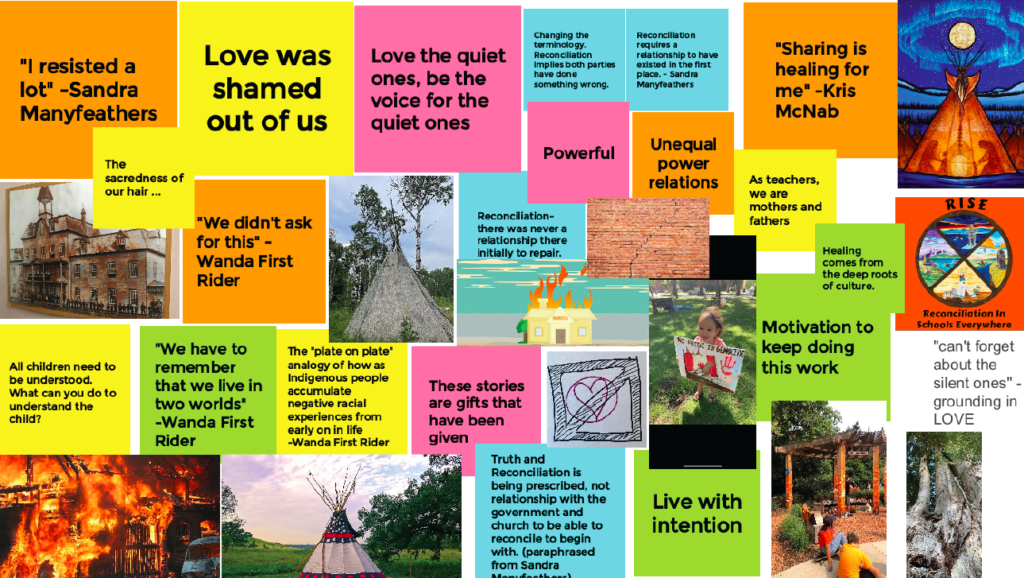

After closing the 2021 school year with several commemorative events to recognize emerging news of the unmarked graves at Kamloops residential school, it was fitting to also begin our Call to Action program deepening our learning about residential schools. We were so grateful for three class guests who shared their residential school survival stories: Wanda First Rider, Kainai, Sandra Manyfeathers, Kainai, and Kris McNabb, George Gordon First Nation. They encouraged us to witness and carry the knowledge forward to motivate our work toward a better future together. We were also given access to a presentation by Kainai scholar Dr. Tiffany Prete sharing very detailed archival research about the history of her people before and during the residential school era. During the month of July, I also took in an online Two Spirit storytelling presentation hosted by Pride Canada and the National Centre for Truth & Reconciliation (NCTR), in which individuals shared their reflections and creative productions made through a series of workshops focused on healing residential school and day school experiences.

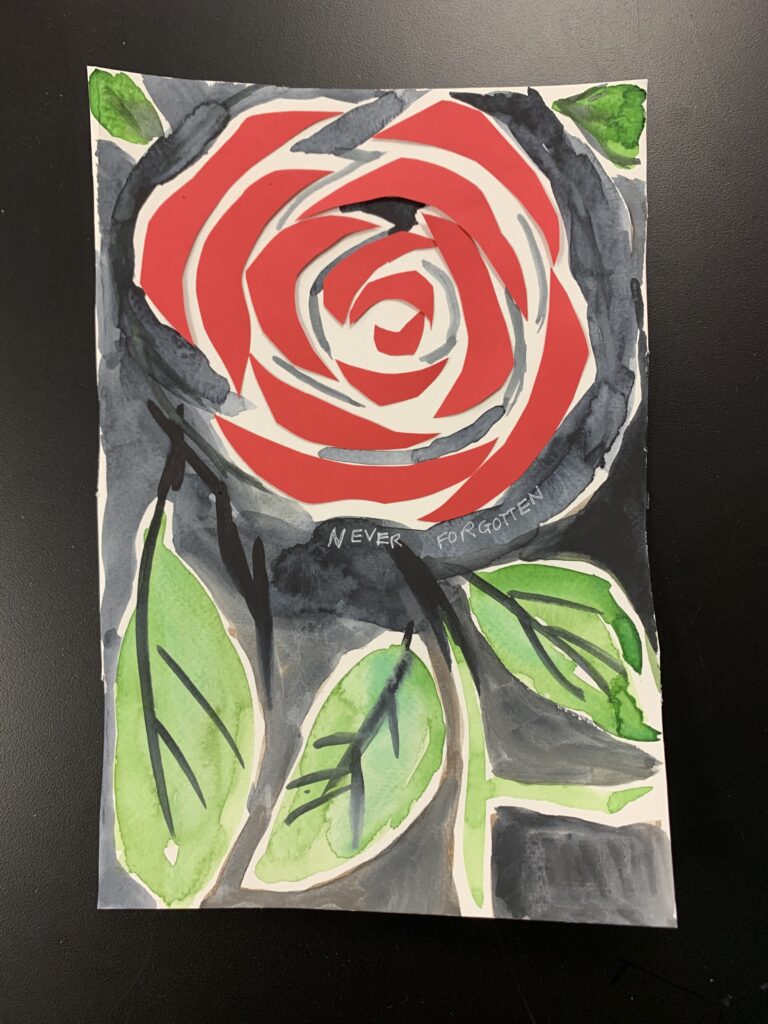

The National Centre for Truth & Reconciliation (NCTR) shares that their spirit name, Bezhig miigwan, which means “one feather,” calls upon us to see each Survivor as a sacred eagle feather. There is certainly sacredness in the stories being shared. The NCTR also affirms that “we are all in this together — we are all one, connected, and it is vital to work together to achieve reconciliation.” As the number of unmarked graves being identified continues to rise, sitting at 5296+ and rising as I write this, I see that we will need to continue seeking new collective ways to witness, and relate to societal grief and guilt to foster momentum toward individual and collective action. With September 30 taking on new presence this year as it becomes the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, we must all carry this new knowledge with honour and commitment to the work ahead.

There were certainly themes that carried forward from the class-based residential school survivor witnessing, and our in-person visit to Old Sun Community College two weeks later. College staff member and Siksika community member Loralee Waterchief was our host and tour guide. She attended Old Sun for a short time as a child while it was a residential school from 1929 to 1971. However, she is now celebrating thirty years in her role with the college in post-secondary support services, alongside the fiftieth anniversary of the college itself.

Loralee gave us a long and generous historical overview before our tour, bringing calm answers to our questions about what to do with the grief and anger that are so natural in learning about these horrific truths. She shared with us that “prayer is powerful, we are all grieving, but we are going to heal, as proper burial will bring dignity and respect to the children.” Notably, she also spoke about fires being set locally and elsewhere in response to current events, guessing that they are not being set by First Nations people, and stating that this “ignorance and bitterness does not help.” This guidance reminds me to be more attentive in future to the common activist instinct to metaphorically “burn it all down,” since healing is actually generative not destructive, and as Loralee reminds us “education is turning negatives to positives.”

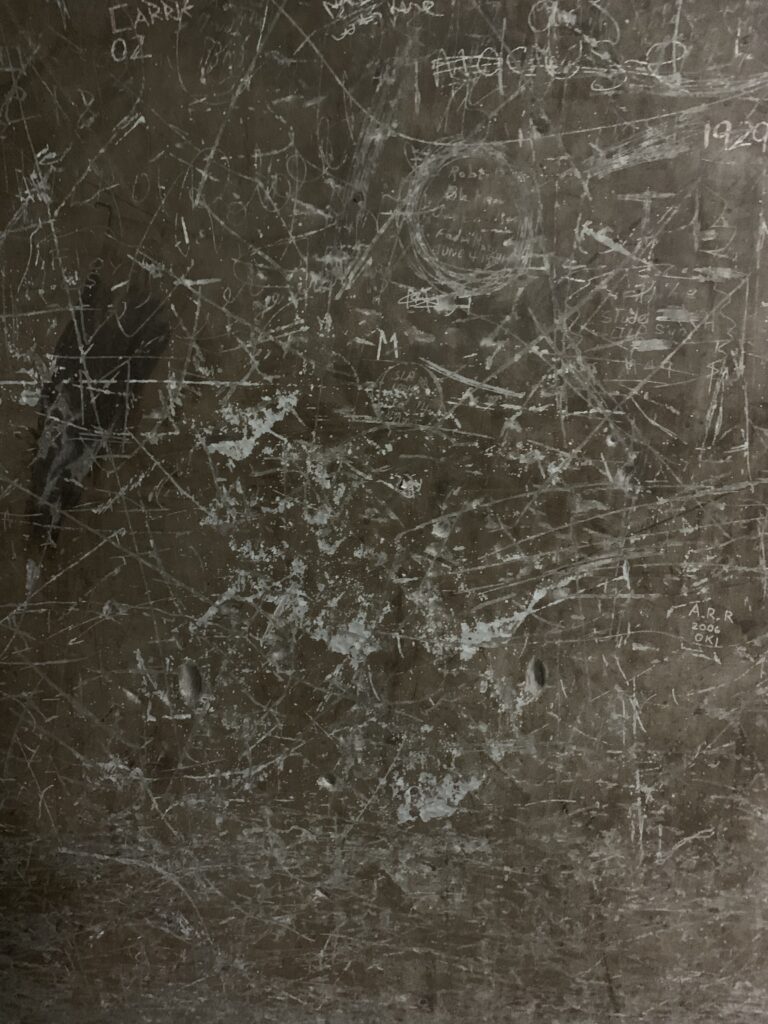

The personal reflection of the residential school tour involved remembering again my first tour there, with Dr. Vivian Ayoungman, Siksika scholar who still helps lead the institution, when I attended with Rocky View Schools professional development in 2017. The learning was memorable, but more emotional than factual. At the time, I did not feel capable of going to the boiler room, a place where children were confined for punishment. I knew I needed to take the extra steps down the hall this time. The darkness and terror of the room is an embodied experience, however brief of what the children felt, as they were treated in dehumanizing and cruel ways. The scratched surface of the door still carries their initials, and their pain. The walls in this school do talk, as Dr. Lyn Daniels and Dr. Aubrey Hanson teach in their profound 2015 collaborative article If These Walls Could Talk.

I am still sitting with the heaviness and horror I feel at what school staff were capable of doing to innocent children. Perhaps there isn’t always something to be done, but rather a living within and around these emotions so that learning can be accompanied, however slowly and imperfectly, by healing and further insight toward action.

The Call to Action in-person learning days also offered us the opportunity to gather and grieve through a red dress ceremony and installation at the University of Calgary campus, connecting to the REDress project initiated by the artist Jaime Black. This is learning that integrates with consciousness-raising initiatives I have been involved in over the past several years in my area. I thought about community members and my students, who have been long committed to bringing awareness to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and 2SLGBTQQIA+ people. I thought about a friend and her family who are grieving missing relatives. I purchased and cared for a new dress to leave in Calgary, as a warrior of truth, and some new statement of my learning in my return to the campus where I began my journey to learn the truth. I am grateful to be in company with colleagues, instructors and Elders who bring presence and offer guidance for the profound sadness of these stories and lost lives.

The place I chose for my red dress is central, highly visible in the main outdoor plaza for the campus. This is to represent the intention that this issue needs to be prominent in all our minds. These daughters, sisters, friends and family members are deeply valued and deeply missed. Our society can only be called safe when it is also safe for Indigenous women, children and 2SLGBTQQIA+ people.

I had also thought about the installation location for the dress in relation to insights the artist communicated recently in our community, as seen in this Touchstones Nelson: Museum of Art and History Jaime Black video. She describes the red dresses as serving a dual role, empty, as reminder of loss, but also a powerful presence, teaching and supporting us in doing the work of building awareness. In her vision, they are also “red dress women warriors, really standing up and taking space again, both spiritually and physically… we are taking our place again as matriarchs of our communities.”

With this in mind, placing the red dress next to the arts buildings felt significant, both for me as an artist, and in connection to an artistic family I know who grieve lost loved ones. I was happy to discover that the wind chime sculpture that was there when I was an art student in the 1990’s was still there, with the addition of a powerful bear presence. The dress can draw its power to be seen and awaken passersby from the arts and artists behind her, and from the land, through the wind in the chimes and the spirits of bear and the surrounding trees.

Returning

Remembering what called me years ago to dedicate myself to the work of reconciliation in our country, it was from a place of shock and distress at learning greater detail about residential school history through my Bachelors of Education studies. It was 2013-15 and the TRC was finishing its work. My own daughter was still very young, and thinking of the small children taken from everyone who loved, comforted and guided them, and the heartbroken families left behind was, and still is, devastating. I did not yet have the vocabulary to identify white supremacy, colonialism and imperialism, but saw societal failure all around me, and was enraged by the lies that had formed my education up until that point.

However, also around that time, I was fortunate to be able to take in one of the inaugural arts performances of the Making Treaty 7 Cultural Society. Witnessing such inspiring cross-cultural learning and healing through the arts, and later volunteering for the organization, supported me to turn my anger and sadness into determination. I am grateful for the opportunities I have been given to continue processing new and disturbing knowledge to take transformative action as a teacher, citizen and human being. I am committed to helping others also walk paths of learning and engagement in their own lives and spheres of influence.